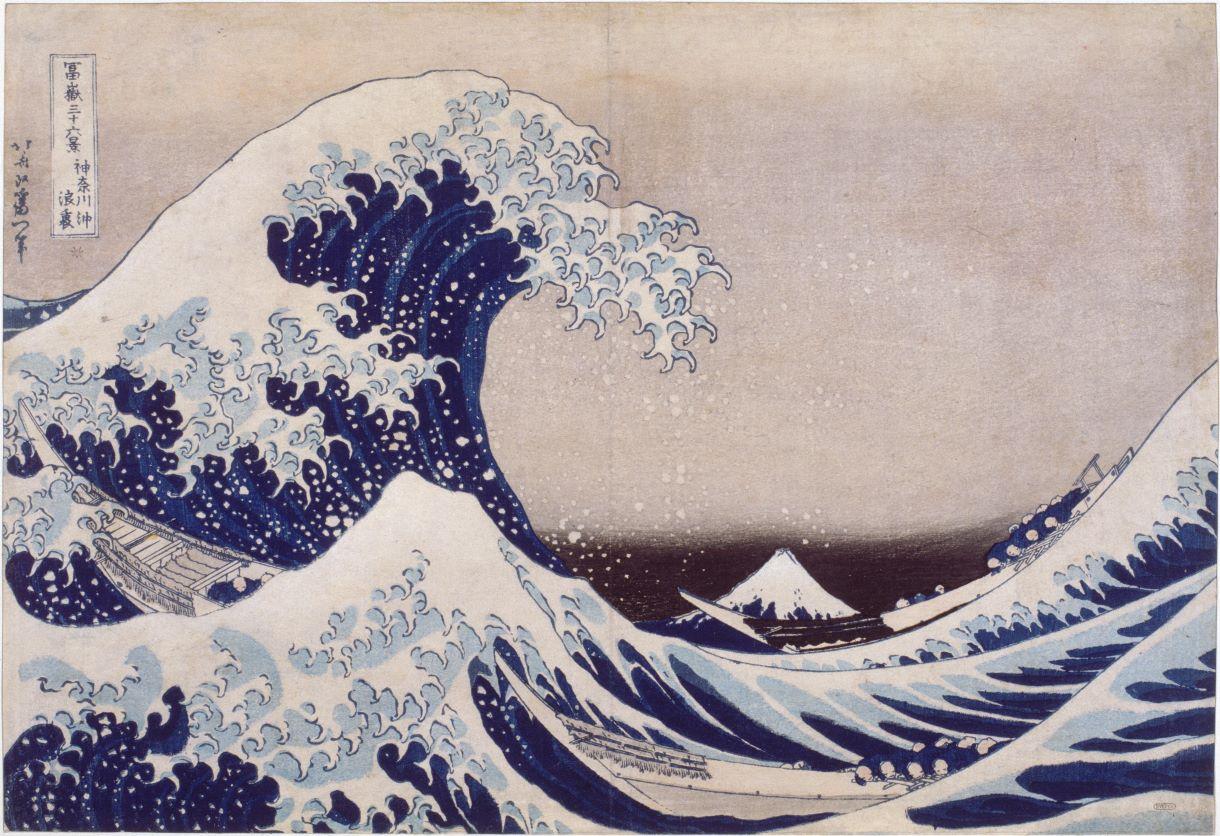

And yet, painted in the very early 1830s, it represents a turning point in the history of engraving on wood in Japan in general and Hokusai’s art in particular. Since the 17th century prints were continually evolving, technically, with the growing number of colours, as well as thematically and stylistically. At first these works with numerous printings aimed at popularising places of pleasure, famous actors, and celebrated courtesans. But that evocation of the “floating world” (ukiyo-e) gradually evolved, both becoming a full-fledged means of expression and acquiring a more introspective dimension. We particularly owe to this brilliant painter and draughtsman, Hokusai, the promotion in the first decades of the 19th century of a new taste for landscape, a genre both ancient, recalling the Chinese painting tradition, and novel, in the ukiyo-e context of this last Edo period.

One aspect of Hokusai’s originality is also his creation of series. The first and most famous is the one that in c. 1830 he devoted to the thirty-six views of the emblematic volcano of the island of Honshu, Mount Fuji, both sacred mountain and highest point of the Nippon archipelago. The near-perfect cone of Mount Fuji is handled with the utmost variety, either central to the composition, or an almost anecdotic detail. In the first print of the series Fuji appears in the background, in the hollow of a monstruous wave with its foam resembling hands about to seize the frail boats tossed by the waters, perhaps suggesting a tsunami. The whiteness of the snow coating the volcano echoes that of the waves, merging earth, air, fire, and water, while the frailty of human existence is played out before our eyes.